한국 문화를 사랑하게 된 스페인 비영리기업 대표 Esther Campos

스페인 비영리기업 대표

Esther Campos

(Versión español abajo)

(English version below)

장애인 고용

장애인 수

– 스페인 : 인구 4천 7백만명명 중 3.8백만명이 장애인

– 한국 : 인구 5천 1백만명 중 2.6백만명이 장애인(2016년 기준)

장애인 고용

– 스페인 : 50인 이상 고용 기업은 2% 이상 장애인 의무 고용

(실제로 법을 지키는 경우가 높지는 않음)

공무원 5% 장애인 의무 고용, 2% 지적 장애인 고용

– 한국 : 300인 이상 고용 기업은 1% 이상 장애인 의무 고용

– 스페인 남부 무르시아(Murcia) 위치

– 70명의 장애인 고용(대부분 지적 장애인)

– 사업분야 : 사무용품, 출판물 등

– 홈페이지 : : https://www.latiendalaborviva.com/

한국 문화 관련 상품 제작

– 2020년 3월 COVID19으로 인해 스페인 전국이 락다운 되었을 때, 팬데믹에 대한 한국의 조치 사례를 조사하던 중 한국 문화를 알게 되었고, Esther Campos 대표가 한국 문화(장애인 고용 포함)에 큰 관심을 가지게 됨

– ‘한글, 보이지 않는 감정, 손가락 하트, 한국의 순례자들’ 등의 한국 관련 책을 출판하였고, 홈페이지 및 아마존에서 판매 중

– ‘한국의 순례자들’은 산티아고 순례길과 제주 올레길를 배경으로 한 로맨틱 스토리

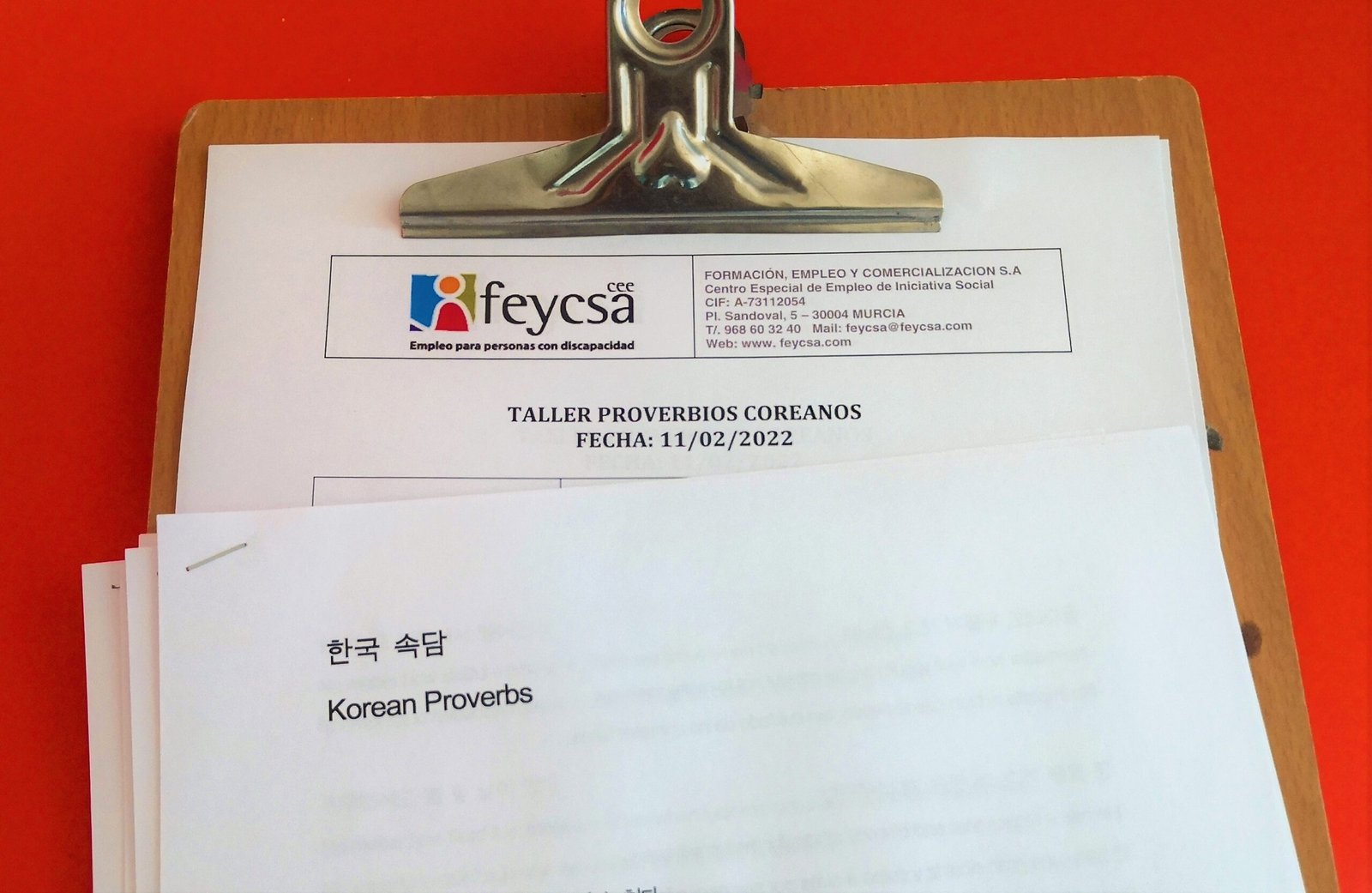

– 한국의 작가들과 함께 한국 속담집 출판 예정

장애인 공평에 대한 생각

– Equality(평등)이 중요한 것이 아닌 Equity(공평)이 더욱 중요함.

– Equity(공평)은 모두에게 동일한 대우가 아닌 각자에게 필요한 만큼 주변의 지원이 필요하다는 것.

– 한글의 창조 또한 한자를 모르던 백성들을 위해 세종대왕께서 창조하신 것처럼 기술의 발전도 장애인들에게 도움이 될 수 있는 방향으로 가기를 희망

Trabajadores con discapacidad aprendiendo sobre la cultura coreana

Uno de estos centros se llama FEYCSA y está situado en la Región de Murcia. Da empleo a 70 trabajadores con discapacidad en su mayoría intelectual y con problemas de salud mental, a través de una continua innovación en sus líneas de negocio: Digitalización y gestión documental, Servicios medioambientales, Artes Gráficas, Papelería y Regalo personalizado, que comercializa a través de sus tiendas, tanto física como online www.latiendalaborviva.com

FEYCSA, a raíz de la pandemia y el confinamiento, descubrió la cultura coreana.

Todo comenzó en marzo de 2020, cuando se aprobó el decreto de confinamiento en España. Ante la falta de información sobre el Sars Covid19, uno de los trabajadores con discapacidad intelectual, muy aficionado al Taewondo, decidió recopilar los videos y entrevistas que sobre este tema existían en internet de médicos y especialistas de Corea del Sur sobre pandemias, para ayudar a la dirección a tomar decisiones en tan difíciles y confusos momentos.

AUTOR:

Esther Campos (seudónimo de Elena Díaz)

<English version>

EMPLOYMENT AND DISABILITY

Some facts about disability in Spain and South Korea

3.8 million Spanish men and women have disabilities. This figure represents 9% of the Spanish population, according to CERMI (Spanish Committee of Representatives of People with Disabilities). This Committee brings together more than 8,000 non-profit organizations, promoted mainly by the families of people with disabilities, to advance the recognition of their rights and achieve full citizenship with the rest of the components of society.

2.6 million Korean men and women have disabilities. (National Disability Survey 2016)

Spain has in round figures 47 million inhabitants and South Korea just over 51 million, with the result that possibly the disability recognition systems have differentiated scales: In Spain, a person is considered to have a “disability” from a -social- handicap of 33% concerning an average person, having a different system to evaluate their level of dependency. The Korean system evaluates disability in a range of severity from 1-7 with a more -medical- vision, attending more to their dependency needs than to their social inclusion needs.

Spain has advanced legislation in social inclusion within the European Union and worldwide. It was already very progressive when the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was published in 2007, the drafting and ratification of which South Korea stood out, with Ban Ki-moon as Secretary-General at the time.

The Spanish Constitution in 1978 already obliged the public authorities to promote formal equality – the granting of equal rights and duties – and material equality- which obliges them to remove practical obstacles so that legal equality is possible.

Based on this material equality, systems of “positive” discrimination have been created that favor people with disabilities in all areas of their lives, from education, health, training, employment, and the right to leisure. The general principle of universal accessibility of products and services for all citizens applies in all these areas.

Non-profit companies set to employ people with disabilities

Perhaps, of all the challenges, labor inclusion is the most difficult to achieve.

Currently, in Spain, there are two models. On the one hand, direct integration into the open labor market and, on the other, integration into the protected market through special employment centers.

In order to favor ordinary integration, public and private companies with 50 or more permanent employees must employ some workers with disabilities of no less than 2% of their workforce. It was established by the “Law 13/1982 on the Social Integration of the Disabled (LISMI), replaced by the 2013 Consolidated Text of the General Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and their Social Inclusion”.

In South Korea, there is a similar obligation in the “Act on Measures against Discrimination of Persons with Disabilities” passed in 2008, but as I believe, this obligation is for companies with more than 300 workers and is only complied with by 1%, resulting in little outcome in practice.

Also, the Public Administration in Spain must reserve 5% of civil servants and labor staff positions and an additional and differentiated quota of 2% for people with intellectual disabilities. This measure allows them to not compete with other people with other disabilities that have nothing to do with cognitive accessibility. In this way, the constitutional principles of merit and capacity are complied with, adapting the contents of the syllabus through an innovative system called “easy reading,” which was validated through an experimental program called “Proyecto Ciudadano” (Citizen Project).

However, given the low incidence of companies’ compliance with the reserved quota (it is estimated that only 20% of Spanish companies comply with this quota), since the year 2000, there is also the possibility of taking advantage of the Alternative Measures Decree, among which the contracting of goods or services with special employment centers that employ people with disabilities stands out.

The Special Employment Centers were also created in 1982 and have been crucial to advancing the labor rights of people with disabilities in Spain. They are social economy companies that make economic viability and market participation compatible with their social commitment and must employ at least 70% of the total workers with disabilities.

In addition to providing paid employment to these people, the Special Employment Centers guarantee training and permanent support in their personal and social life.

In Spain, some 800 Special Employment Centers employ more than 80,000 people with disabilities.

Each Special Employment Center chooses which activities to carry out and its support services according to the interests and needs of the disabled workers it serves and the business opportunities they find or suggest to them.

Workers with disabilities learning about Korean culture

One of these centers is called FEYCSA and is located in the Region of Murcia. It employs 70 workers with disabilities, primarily intellectual and mental health problems, through continuous innovation in its business lines: Digitalization and document management, environmental services, graphic arts, stationery, and personalized gifts, which it sells through its physical stores and online; www.latiendalaborviva.com.

FEYCSA, as a result of the pandemic and confinement, discovered Korean culture.

It all started in March 2020, when the confinement decree was passed in Spain. Given the lack of information about the Sars Covid19, one of the workers with intellectual disabilities, very fond of Taekwondo, decided to compile the videos and interviews on this subject that existed on the internet of South Korean doctors and specialists on pandemics, to help the management to make decisions in such complex and confusing times.

In addition to thanking those tips and putting them into practice due to Google’s algorithms, the CEO started receiving recommendations to watch Netflix series produced by South Korea, something she had never done before.

In the Korean dramas, the topic of disability was addressed in a very similar way to the Spanish one, highlighting the values of intelligence and emotional development.

From this immersion in Korean culture, projects arose for the graphic arts line of the Special Employment Center as part of a project of immersion in Korean culture and understanding of the “Hallyu.” Thus, the center published a novel for solidarity purposes entitled “The Korean letter; the invisible emotion,” which told the discovery of Korean culture through K-dramas and its beneficial effect on emotional health, whose dedication is a tribute to the team of creators of the k-drama “Chocolate,” set in a hospital for people with terminal illnesses where a surgeon and a chef, with acquired disabilities, struggle to continue working and being useful to their fellow men and women.

The interest in Korean culture is still alive in this small company from southeastern Spain. A second book, “The Pilgrims of Korea,” will be published in March 2022. The novel is a romantic story connecting the pilgrimage routes of Liébana, Santiago de Compostela, Caravaca de Cruz, and Jeju Olle in South Korea. It also introduces the figure of St. Andrew Kim Dae-geon and the origin of Catholicism in South Korea to the Spaniards while explaining why Koreans are already the eighth nationality in pilgrims who make the traditional Way of St. James.

In addition, with the collaboration of Korean poets and painters and other Spanish artists, they will launch some notebooks with a selection of Korean proverbs that, like Spanish proverbs, can help others find the resilience needed to overcome the adversities of everyday life.

It is essential to raise visibility and awareness for inclusion in the workplace. No matter how many laws are enforced to provide opportunities, integration cannot be imposed, and sanctions do not help to have faith in the abilities of people with disabilities.

Emotions are a universal language and many K-dramas that deal masterfully with mental health and disorders such as autism, like the acclaimed “It is Okay To Not Be Okay,” schizophrenia, like “It is Okay, That is Love,” and the autonomy and employment of people with disabilities like in “Moved to Heaven” would also help Western audiences.

It would be desirable that these productions would jump from platforms such as Netflix and from the vision held about them of Asian romantic dramas to the consideration of productions that could be in prime-time in Spanish homes through public television whose mission is to promote inclusive values.

Inclusion is a slow but unstoppable change of mentality, which must occur in all areas of society and reach all groups. It is a fight against discrimination based on disability and race, gender, religion. In this sense, labor inclusion allied with Corporate Social Responsibility policies and the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda are achieving more remarkable progress than the Government’s social integration policy alone. On the other hand, the Spanish experience could help South Korea.

The need for “positive discrimination” or material equality must be insisted. For Spanish law, which draws its sources from Roman law, positive discrimination is based on the general principle of the jurist Ulpiano who said that “Justice is not to treat everyone equally, but to treat each one as he deserves” therefore, justice needs equity; giving support to all, yes, but to some more than others according to their needs.

Finally, people with disabilities must not miss the train of new technologies because it is precisely thanks to them that they can overcome cognitive barriers that were unthinkable in the analog era. Like Hangeul alphabet was an inclusive invention based on a scientific method (the study of human phonation) that overcame the cognitive accessibility of Chinese ideograms. In this sense, it is reminiscent of systems such as Braille or sign language, which have changed the lives of people with visual and sensory disabilities, current technology allows people with intellectual disabilities to handle complex computer programs, translate from unknown languages, not only from English but also from Korean with applications as simple to use as pagago. Naver and to have no limits other than those we still allow to exist on their way to a normalized life as we each wish it to be.

Esther Campos (pseudonym of Elena Diaz).